LISTEN TO THIS ARTICLE:

Adolescence is a confusing, hormone-driven, bumpy ride even in non-pandemic times. “Quaranteenagers” are those teenagers who lived through the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the past years they had to navigate fear, anxiety, depression, remote learning, social isolation, race-related protests, and widespread grief.

First aid for teenagers’ mental health going forward involves helping them heal psychologically and emotionally. Researchers admit that “while the knowledge base regarding children’s responses to trauma and adverse events, in general, has been expanding, descriptions of their responses during epidemics remain scarce.” We don’t need numbers and statistics to tell us what we already know: This year teens and their parents have faced unparalleled levels of mental health distress.

Newfound threats to adolescent mental health

COVID demolished the security that we all took for granted.

The COVID-19 pandemic posed multiple unique threats to teens. First and foremost, it completely destroyed any semblance of ‘normality.’ It brought constant stress that is only now starting to ease after a year and a half. There was never any reason to think that the world they had when they were young would remain relatively the same as they aged. COVID demolished the security that we all took for granted.

Teens bore the brunt of this. They went from social school days, care-free weekends, and gatherings with friends to total lockdown. Worse yet, they had to continue learning at home alone, all the pressure of school without the benefits of seeing friends. Every aspect of their lives that didn’t already revolve around screens immediately demanded technology. COVID served a heaping helping of strife while deleting from their lives any semblance of structure and support.

Psychological burdens

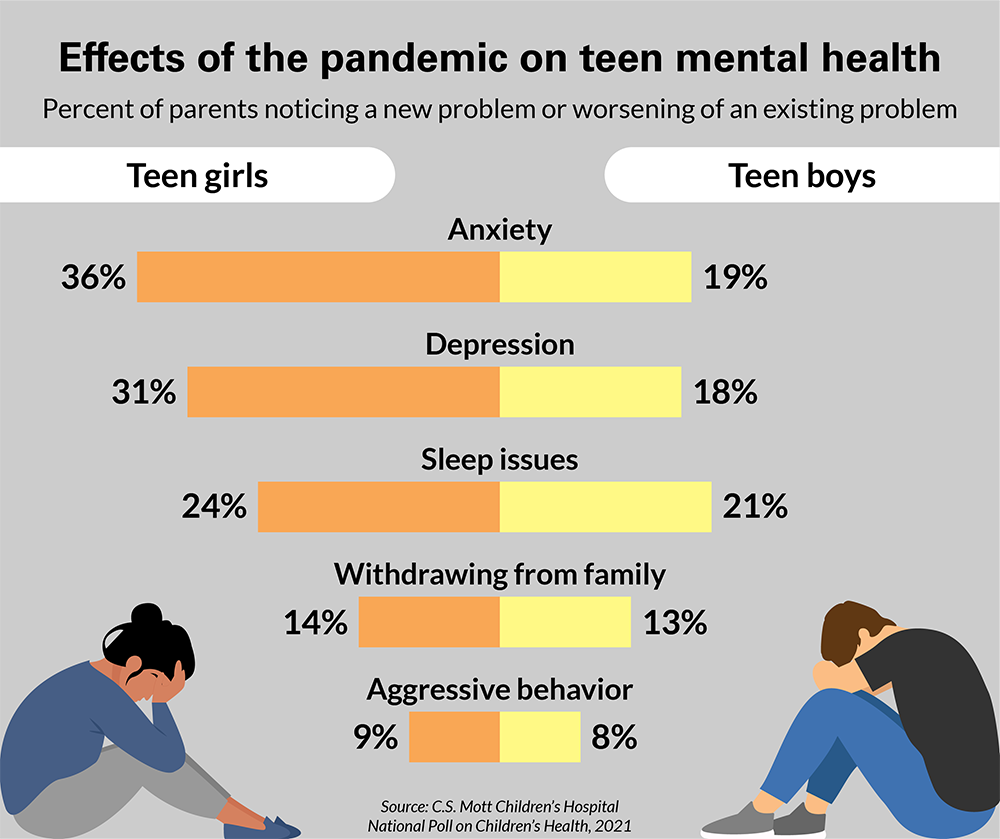

Teens thrive when they have a sense of security, routine, and control. Of course, they have not had any of these since March 2020. Nearly half of all U.S. teens experienced new or worsening mental health conditions since the start of the pandemic. During the pandemic, anxiety and depression have skyrocketed in children and adolescents.

- 6%-43% report depression

- 9%-37% report anxiety

- 31% report both anxiety and depression

- >50% report moderate to severe impact of the pandemic on their mental health

Anxiety and depression have led teenagers to avoid school and withdraw from their hobbies. Those who didn’t detest school poured themselves into it with a hyper-focus on perfection. Many teenagers found themselves irritable, emotional, and needing extra reassurance from parents. “Meltdowns” and panic attacks became increasingly common, and the fear of teenage suicide looms large for many parents as they try to keep teens safe.

It is heartbreaking to watch your kid go through this. I feel like we have tried everything- medicine, therapy, essential oils, working next to her, weighted blankets, timed work periods, and more. March and April were the worst- including a night where her friends reached out to me saying they were worried about her safety. She was over a month behind in her assignments, having panic attacks late at night, and feeling depressed. – Mother of 16 year-old “C”

Physical symptoms

Pandemic-related anxiety and depression manifested as other types of problems such as sleep disruption, withdrawal from family, aggressive behavior, substance use, self-harm, and disordered eating.

Isolation caused by social-distancing precautions potentially hastened the onset of some teenagers’ mental health problems. For many teens, emotional distress presented as stress-related physical symptoms. Upset stomach and lack of appetite struck many, along with diarrhea and constipation. Headaches and nightmares were also common.

Unequal distribution of mental health risk

Each teenager experienced and will process living through the COVID-19 pandemic differently. Some are at greater risk of long-term mental health harm. One in six teens were already living with a mental health disorder before the pandemic began. Prior to the pandemic, one in five teens had a parent experiencing a mental illness such as anxiety or depression. These teens are at greater risk of developing a mental illness themselves. This study also found that COVID-19 threatened other teens already at greater risk for mental health challenges:

- Youth with pre-existing mental health conditions

- Teen members of families and communities of color

- LGBTQ+ youth

- Adolescents with learning disabilities

- Teens living in families impacted by violence, substance use, or parental mental illness

- Adolescents with lower social and economic resources, particularly those with limited access to reliable internet for remote school

Disrupted development

Our brains go through important maturation during adolescence and do not stop developing until around age 24. Childhood stress can change brain development and change how the body responds to stress long-term. Traumatic experiences early in life can negatively impact mental and physical health well into adulthood.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, teens need to recover from a kind of post-pandemic distress. Overnight they lost the structure, routine, and social supports of ‘normal’ life as they knew it. Unemployment, housing, and food insecurity skyrocketed during the past year and a half, adding to both family and adolescent stress.

Pandemic associated-grief

Part of the human response to trauma is grief. No grief is simple, but pandemic-related adolescent grief is particularly complex. Many teens have had to cope with family members getting sick or dying from COVID. For many, this may have been their first experience with death. Even as adults, we are struggling to deal with the devastating numbers of lives lost in this past year. Without hospital visits for sick family or normal funeral services, grief has been even harder on us.

Pandemic teens are also grieving the loss of milestones on their road to adulthood. Adolescence can be an important time for religious, social, and cultural rights of passage. Think birthday parties, quinceañeras, getting a driver’s license, going to prom, taking the SATs, and attending graduations.

Teens feel a true sense of loss for missing out on important affirmations that remind them they’re growing up. -Berkeley Center For the Greater Good

Remote learning vs. mental health

With remote learning, teenagers became bored and lonely at home. They felt exhausted by long hours in front of a screen or panicked about possibly missing out on important learning. Levels of student engagement with learning reached record lows during the pandemic. In addition, unreliable internet among economically disadvantaged youth further deepened educational disparities.

Teenagers’ mental health and pandemic academic challenges became intertwined in a downward spiral for many teens.

I developed depression, it was really hard to motivate myself to get work done and I was often working late into the night on homework- like 2 or 3 in the morning. I would often be a month behind in work in at least 1-2 classes. This made me really stressed, it made me so stressed that I couldn’t do any work and it would lead to me having panic attacks sometimes. – Anonymous, 16 years old

Many teens worked extra jobs to help support their families and remote school made multitasking more feasible. Working high school students are at greater risk for stress, disengagement, and dropping out. The National Dropout Prevention Center predicts a doubling or tripling of students falling behind academically and leaving school.

School was the one place many at-risk youths had a chance of being noticed and offered help. Disruptions in school services have been particularly harmful to adolescents with ADHD and Autism Spectrum Disorders. They have been less able to adjust to lockdown changes, alterations of routines, habits, and rituals. It can lead to increased acting out behaviors and behavioral problems.

Overwhelming social isolation

Adolescence can be a lonely time, especially among students who are perceived as “different.” It might be their physical appearance, disability, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, or religious beliefs. Social isolation in teenage years can influence growing brain pathways necessary for a lifetime of healthy social connections.

Public health research shows that socially isolated youth are at a greater risk for depression, anxiety, self-harm, suicidal thoughts, and substance misuse.

Young people rely more heavily on social relationships and connections for emotional support than adults or younger children may. If they are unable to spend enough time with peers, they feel lonely, isolated, and depressed. That’s how teenagers gradually separate from their families and discover a sense of identity.

During the pandemic, parents reported that their teenagers texted (64%), used social media (56%), played online games (43%), and talked on the phone (35%), every day or almost every day. Very few teens got together in person with friends daily or almost every day, indoors (9%) or outdoors (6%).

Excess screen time

We don’t know how well socializing online replaces in-person contact in terms of meeting teens’ social needs. In fact, the loneliness paradox suggests that social media actually increases our loneliness. According to one survey, half of the people attending virtual social gatherings did not feel any less lonely. Ten percent of attendees actually felt more lonely after the virtual social gathering.

The pandemic isolated adolescents from their usual sources of support, connection, and healthcare.

Pandemic precautions also disrupted access to mental health services. Before the pandemic, one out of every three teens receiving mental health services obtained them through their schools. Now, teens don’t have the usual stress outlets such as sports, community service, and other extracurricular activities.

The pandemic rapidly overwhelmed our nation’s already limited supply of mental health care providers for teens and adolescents. In fact, ERs around the country reported an increase in visits from young people with mental health concerns. Even before the pandemic, half of teens with mental illnesses did not get treatment from a mental health professional.

Quaranteenagers in survival mode

Teenagers and their families have been living for more than a year in “survival mode.” In reality, we don’t know what the future holds in terms of COVID-19. However, what we do know is that today’s teenagers are different because they survived adolescence in a pandemic. Surely, though, adults can help teens find their way back to safety and emotional wellbeing from their pandemic experiences. They can teach mental health literacy and coping skills and help them restore social connections and structure.

1. A learning opportunity for mental health literacy

Processing difficult emotions or experiences requires you to be able to name them and talk about them. Prior to the pandemic, teens did not receive enough education about how to understand or talk about mental illness.

One silver lining is that many teens are now better equipped to talk about their own mental health. More than ever, they recognize what they need to stay well. The pandemic normalized mental health struggles and seeking help for both parents and their teens.

Another up-side is the massive expansion in resources, online mental health support communities, and remote counseling.

The vast majority of mental illnesses start emerging in the teen years. There’s a lot of confusion that can come with trying to figure out what’s normal vs what might be a warning sign that something isn’t right. And that can be super overwhelming! – Liz Babkin, medical student and teenanger mental health advocate

2. Talk it out

Teaching teens more about mental health gives them the language and the tools necessary for asking for help. Also, it helps them better support struggling friends or family members. NAMI’s “Ending The Silence” video is another educational tool. It can change students’ knowledge and attitudes towards mental health conditions and seeking help. Even more, encouraging teenagers to talk through their anger, fear, sadness, frustration, and loneliness can help them heal.

It is about giving them space to have these conversations on their own time-frame… If teens are wanting to process, validating their experience is important (“That sounds hard. I’m sorry you had to go through that.”) While also be mindful not to minimize how they are feeling, (“You had it good… imagine how it felt to be X?”) or trying not to problem-solve if they are only looking for an active listener. – Jill Frame, LCSW

Validating your teenager’s feelings helps them to develop healthy self-esteem, feel more confident, and learn the practice of empathy. These building blocks of emotional intelligence can pave the way for a healthy transition to adulthood.

3. Cultivate concrete coping skills

Beyond growing mental health literacy, the pandemic forced teenagers to expand the range of tools in their coping toolbox. As an adult, you can help teens see themselves as survivors. To start, help them identify how they adjusted to living in a time of uncertainty, stress, and isolation. In the future, skills and tools they used during the pandemic can continue to serve them going forward.

As adolescents come out of their quarantine shells, help them build a supportive structure with healthy habits and self-care.

- Managing screen time

- Getting enough exercise

- Healthy eating

- Getting enough sleep

- Spending time with others

- Making time to relax

Structure remains a key part of adolescents’ sense of security. Unfortunately, many teens lost their comforting structured existence during the pandemic. Helping them rebuild a scaffolding of activities while prioritizing sleep, exercise, and social connection will provide routine and structure for healing.

4. Restoring social connections

Teens’ abrupt loss of social outlets and peers will impact their return to in-person and group social settings. Socializing in person for many teenagers will entail an expanding social life that can feel terrifying. Even worse, this is particularly painful for teens living with Social Anxiety Disorder or Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

I have been talking to a lot of teens (and adults!) about the strategy of ‘dipping their toes’ back in rather than feeling obligated to ‘full-on jump or cannonball.’ It’s OK to say ‘no’ if they are feeling overwhelmed or anxious and aren’t yet ready to be around a lot of people. Also, it’s important to begin deliberately working towards being more social so as to minimize the risk of increasing anxiety by prolonging social isolation. – Jill Frame, LCSW

Teenagers can become resilient survivors

Living through COVID-19 threatened teens mental health in new ways. Most importantly, it brought prolonged stress, uncertainty, disruption of routine, removal of their coping mechanisms, and increased social isolation. All this challenged teenagers to find new coping skills and ways of talking about their mental health.

In a post-vaccination world, we all are wondering how to heal from COVID-19 mental health distress. Parents and adults can reinforce coping skills teens discovered during the pandemic. We need to keep fighting mental health stigma with advocacy and education like NAMI’s Ending the Silence campaign. To keep those most at risk safe, we need to stay vigilant on our watch for warning signs of mental illness. It may be years until we understand the pandemic’s long-term mental health effects for teenagers. However, today, our job is to stay close, available, supportive, and ready to listen.

Learn

Learn Stories

Stories ID Symptom

ID Symptom News

News Find Help

Find Help

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share

Share